The entire first season of the Netflix series Another Life became available last week, and the series – which starred Katee Sackhoff of Battlestar Galactica fame — employed multiple vendors to create some out of this world scenarios, including CoSA VFX.

Below, CoSA’s VFX Supervisor and Co-Founder Christopher Lance and Lead 3D Artist Dustin Colson share some behind-the-scenes look at the Netflix sci-fi thriller.

Can you talk about the creation of the ship and how it was implemented into the show?

CHRISTOPHER LANCE: Initially, the ship was just a ring, that then became the base of the artifact, and then the crystal [would] grow out of it, but the clients wanted something more interesting for when it was flying, and rightly so.

DUSTIN: The client actually put forth the concept that this was something completely unprecedented, a ship the likes of which hadn’t been seen before, so they sent us a gif of a Möbius strip in motion. A couple of our supervisors – Alex Cancado and Brian White – combined that concept with our artifact base model…and now we’ve got the Moebius.

Does it take longer to render something with that many moving parts?

DUSTIN: Actually, no. For what it is, rig-wise and everything, it’s a deceptively simple object. The hardest thing is catching it at the right angle. You actually have to show the Moebius in the right angle or it looks very awkward and oblong, if you don’t get it from the proper angle to give it the infinity look. Otherwise, it’s this weird cartoonish looking ring, I guess you could say, but beyond that, moving in on itself and everything was actually quite easy to get it to render.

CHRIS: You guys in 3D he had to manipulate the Moebius for every single shot to make it look pretty.

DUSTIN: Yes. It has to show its best face to camera.

How did CoSA work alongside other vendors on this show?

CHRIS: We had the pleasure to work with a great VFX supervisor, Mark Savela, on this project. He and Kerrington Harper, his producer… they coordinated all of the work among us and several other vendors. So there were a couple times when we shared assets. [As an example], it was great working alongside Atmosphere on the Salvare, which is the main ship that features throughout the season.

How difficult is it to create things like the plasma wall arcs when they’re actually behind somebody, and it’s already been filmed?

DUSTIN: That’s really just a lot of rotoscoping, and faking interactive lighting.

Is it correct that CoSA had artists working on this project in both L.A. and Vancouver?

CHRIS: Because we have a very talented people in both Los Angeles and Vancouver, and we’re accustomed to working on multiple shots together. It was a seamless handoff, back and forth. We had our Vancouver team, on the phone and sharing screens in dailies, sharing assets, so that that really helped smooth the fact that there are multiple people across different locations sometimes working on the same shot.

There are a lot of a screen burn-ins that I noticed in the first two episodes. How has that process changed over the years?

DUSTIN: Burn-ins, per se, are only as hard as the shot they’re in. If you have something blocked off, yeah, that’s easy. But then if you’ve got a guy sweeping across the room, blocking the screen with fine hair detail, that can be time consuming and kind of a pain to match your motion blur and things of that nature.

CHRIS: Years ago, whenever there was a burn-in on a screen, a visual effects supervisor would require that screen to be lit up green. Nowadays, I actually ask people to not put anything on the screen, because that way, if the screen is dark, we can retain reflections and bring them back at any opacity that we want. If it is lit up green, that then casts green interactive light on actors, on the bezel, etc., that we then have to remove. It actually creates more work for us. The only time I would request green on a screen on which that we’re going to do a burn-in on is if you have an actor’s hair in front of the screen, or perhaps an over the shoulder shot where you’re seeing their out of focus hair, because that’s often really difficult to do if it’s not lit properly.

DUSTIN: Or there’s times will ask for tracking markers, or we’ll put a little dot, and we’ll track that dot, so when it is moving, it’s easier to hold on to things of that nature.

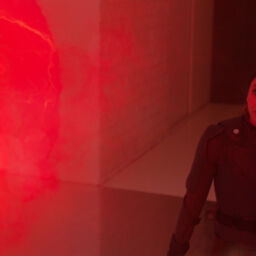

In the second episode, there’s a moment where a glow is coming from the artifact onto the actors. Was that practical or something you guys added in the post side?

DUSTIN: I actually think that was part practical and part us, because they did have some interactive lights that they had on set that the artifact itself covers in the plate that turns on. I think we added some as well.

CHRIS: That interactive light was key, because I think those shots turned out brilliantly, They looked really, really beautiful, and it was because Mark and the Cinematographer worked together to supply us with interactive light. There were a lot of lens flares too, which added immensely to those shots and made it look like that artifact was really there.

So can you talk about creating the alien planet landscape?

CHRIS: I believe they shot in an abandoned quarry, and we basically did a 2.5D set extension on all sides to make this quarry look like it extended in all directions, and we did a huge Houdini simulation for the pyroclastic storm that comes over the horizon, bearing down on them.

I understand the Artifact required a lot of rendering time because there were a lot of elements at play. Can you talk about that?

DUSTIN: It was an undertaking, to an understatement. With what is considered to be one of the fastest rendering softwares currently out, Redshift, we were still hitting sometimes 10-hour render frames. From a geometry standpoint, it took a lot to build because of its sheer size. The lookdev wasn’t a whole lot because we just had to make a crystal shader, but now getting something like that to refract the light from its environment, it became a very large undertaking.

I mean, our team did amazing with CG. We still managed to get out renders. Comp worked with us beautifully. We worked hand in hand with Comp and the Environments team working out multiple passes and ways to get things to refract, to look like it was alive, and moving, and doing things. But after months of trials and tribulations, we did get it out.

Can you talk about the pyroclastic storm in Episode 102?

DUSTIN: That was a multi layered sim from effects. I think we ended up doing, like, three or four layers that Compositing then put together. We had to do deep rendering, because we were having issues with our shuttle not getting in there well, and really sitting in, showing that it was really within that pyroclastic cloud and being overtaken. But yeah, I think we had two or three guys on that, that put out multiple passes in Houdini. We had to render Deep, which is a little more of an undertaking, and really work with Comp to get that shuttle in there and look like it was truly being impacted by that pyroclastic cloud when it hit.

Deep is highly more render intensive, essentially, because you’re rendering in full three dimensional space. You’re not rendering flat, so you can essentially stick things in there and can be affected by that object.

What are the biggest challenges in doing a project like this one?

DUSTIN: The amount of rendering.

Complex 3D objects like the Artifact and the pyroclastic cloud are render intensive in everything from calculation, to the amount of space they take, to the amount of time they take to render.

CHRIS: Looking at the pyroclastic storm, people might think “wow, that would take an intensive amount of render time.” And while it certainly did, I think the Artifact itself] belies how complex it actually is. It’s just sitting stationary in a field, right? It’s not like a giant monster, but it’s got refraction, and reflection, and an insane number of polygons; rendering realistic lighting on a colossal crystalline object like that is daunting.

DUSTIN: We actually could not open a scene with it in. We had to proxy it into sections and rebuild it from proxies, just to be able to physically open a scene and work with it. I think it was somewhere in the neighborhood of 300 gigs of geometry.

Is there anything else you would like to say about this project?

CHRIS: Just that it was a joy working with Brian White (CG Supervisor), Eduardo Arroyo (Comp Supervisor), and Nikolai Michaleski (Vancouver Comp Supervisor), along with the production staff and artists, and Mark Savela, the VFX supervisor. I got to know some of this team really well. I don’t think you and I had worked together this closely before this, Dustin, but it was a pleasure.

DUSTIN: We got to create some beautiful things that were very out of this world.

CHRIS: There are some really, really great shots in there that I’m really happy with, and we got to work on some really amazing, beautiful shots with really talented artists and supervisors, both in CoSA and outside of CoSA.

DUSTIN: I would definitely say it helped CoSA grow.

Another Life is now available on Netflix.

ABOUT CoSA VFX

Founded in 2009, CoSA VFX has grown from a small boutique into a thriving visual effects studio with offices in Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Vancouver. The CoSA VFX team has received Emmy nominations and wins for their work on TV series including Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Almost Human, Revolution, and Gotham, and currently provides visual effects for multiple studios, networks and streaming television services.

FOLLOW CoSA VFX

FOLLOW CoSA VFX

http://cosavfx.com

http://facebook.com/cosavfx

http://twitter.com/cosavfx

https://www.linkedin.com/company/cosa-vfx/

MEDIA CONTACT

Craig Byrne

Publicist/Social Media Manager

Craig.Byrne-IC@cosavfx.com